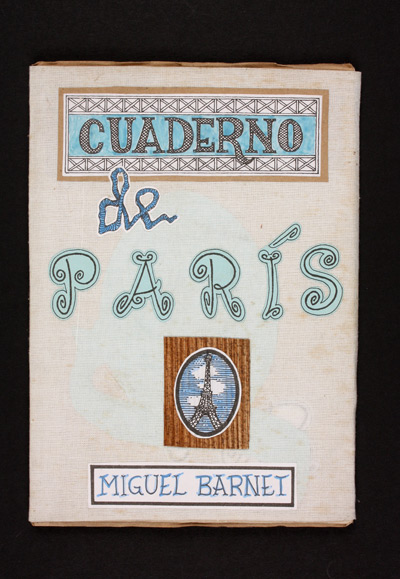

Cuaderno de París [Notebook from Paris]

by Miguel Barnet

Rolando Estévez Jordán (designer and draftsman)

Matanzas, Cuba: Ediciones Vigía, 2003

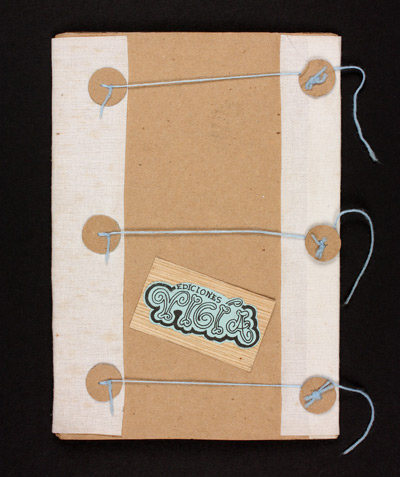

Photocopies on paper with watercolor accents, cloth, and yarn

Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri (2009.69)

Gilbreath-McLorn Museum Fund

Juxtapositions of Cuban and Parisian imagery are held together by tightly bound blue strings around a porous, white cloth enclosure. The scrapbook-like composition of natural, fibrous pages of text is divided throughout the structure by dark, thick pages covered in pen and ink illustrations. Irregular cobblestones, which can be found on the streets of both Cuba and Paris, are a unifying texture while the distinguishing icons of the palm tree and the Eifel Tower are interspersed throughout. Just beneath the soft cover is an interactive pop-up that intertwines the icons into a singular form with extensive roots on a winding cobblestone path.

The concepts of travel and trade are extremely important for the isolated natives of Cuba, whose geographic location is ideal for the international exchange of both goods and knowledge. This piece shares the story of a dualistic struggle that many Cubans experience in their life: the controversy between their true national identity and that which the government portrayed during the Cuban Revolution, the way natives perceive themselves and the commercialized images circulated through Cuba’s most valuable economic resource, tourism. Author and editor Estévez combines his illustrated content with the written words of Afro-Cuban scholar, Miguel Barnet, one of few Cuban citizens to leave his homeland, seek education outside of Cuba and return to share that knowledge with natives. It is simultaneously an invitation to explore the vast cultures of the world and a caution against forgetting what Cubans know as their authentic identity.

by Lyria Bartlett

Three blue strings, reminiscent of the sky often depicted within, wrap the entire structure of this piece and secure tightly around the back, indicating that there may be loose items or additional pages not traditionally bound (i.e. tickets, brochures, other ephemera of tourism). Less substantial, lighter-hued text pages complement the use of a thick, natural material for the binding and dividers that isolate distinct sections of the book. Each text page contains a strong border of steel structural elements on the sides, a tilted Eifel Tower, palm trees floating on clouds above and cobblestone corners. The beginning letter for each entry is largely scaled – as in an illuminated medieval manuscript - and filled with a cobblestone texture. Each divider uses cobblestones in some manner with striking black ink: towards the beginning they are used as a pattern that would likely be seen on roads in both Cuba and Paris, and later as framework around oval windows. The vistas through the windows progressively indicate a journey to Paris, the feeling of being an outsider or extreme naïveté, caged on the interior with freedom beyond, attempts at existing between two opposite worlds, and a refined man returning to Cuba with his mind remaining in Paris. In the final divider, the barrier has been broken between the interior and exterior of the window. The well-to-do man sits a top an arch, holding the Vigía lamp, under which water flows between the two worlds.

The continued use of cobblestones, Parisian and Cuban identifiers reinforces the designer’s desire to connect the two disparate locations. “Cuba’s position at the center of one of the most frequented maritime routes in the Americas opened it to a constant flow of news, ideas, inventions, and products of all kinds. This openness to the outside world was further stimulated by extensive study abroad.”1 Simultaneously, however, the constant struggle to maintain/create a purely Cuban identity led to conflicts between those that left Cuba and those that remained. Tourism and the propaganda that accompanies the industry continue to be a huge moneymaker for Cuba, although many natives consider it to be a faux-representation of their homeland. The search for significance and advancement in their country has resulted in a common quest for diverse cultural knowledge. Although expensive traveling and direct physical contact with other cultures is not possible for many citizens, mental excursions are abundant. Dreams are necessary in Cuba and this manuscript appears to be documentation of one native’s journey.

Designed by Rolando Estévez Jordán in 2003, this Ediciones Vigía publication further reinforces the dualistic nature of Cuba by publishing controversial writings of Miguel Barnet (b.1940) in a travel-log format. Tourism is recognized as a part of Cuba’s identity, however, the realistic depictions of a native’s perspective beneath the government’s filter is also given. A strong, perhaps longing, relationship between the isolated island of Cuba and the thriving academic and artistic atmosphere of urban Paris is depicted. The consistent juxtaposition of Cuban and Parisian iconography – the Eifel Tower, the palm tree with extensive roots, the Ediciones Vigía signature lamp, cobblestones and water - suggests a tension between cultures, geographies, values and ideals. The interactive notebook, diary or traveling sketchbook format of this compilation gives the viewer a feeling of simultaneously protecting and fantasizing about a particular experience.

Barnet is given credit for the publication with his name prominently featured on the cover while Estévez places his name amongst other credits in the back. The former is known for his connections to El Puente publishing group – banned in 1965 - and his ability to narrowly escape governmental sensors through the use of creative writing and symbolism during the Cuban Revolution. It seems that Estévez’s choice to publish the work now is an attempt to recover a certain level of truth about Cuban identity and the suppression of many opinions by the Cuban government. Barnet was born in Cuba and partially educated in the United States before returning to his homeland, a circumstance that has historically caused many Cubans to be viewed as traitors. Through his poetry, however, he became a favorable member of the community and an active reporter of cultural and political perspectives in Cuba. He was inspired by his education under Fernando Ortiz – the pioneer of Cuban anthropology and an instructor of many Afro-Cuban culture courses – at the University of Havana. Through his voice, many native Cubans have historically found sustenance uncommon in tourist-focused propaganda.

Cuaderno de París is one of the few Ediciones Vigía publications with an ISBN number, prominently displaying Estévez’s intentions to make it available to an extensive audience via libraries. There were 200 copies made. Illustrating the tension associated with tourism and the importance of cultural knowledge, this travel log simultaneously seeks to find deeper meaning, connections and associations with its audience and Cuban identity. To browse the publication is to take a journey. To read it is to find its significance across a dynamic timeline of Cuban history.

by Lyria Bartlett

(Sources)

Howe, Linda S. Transgression & Conformity: Cuban Writers and Artists after the Revolution. 2004.

Juan Martinez. Cuban Art and National Identity: The Vanguardia Painters, 1927-50. Gainesville: University of Florida, 1994. Page 93.

- 1 Juan Martinez. Cuban Art and National Identity: The Vanguardia Painters, 1927-50. Gainesville: University of Florida, 1994. Page 93.