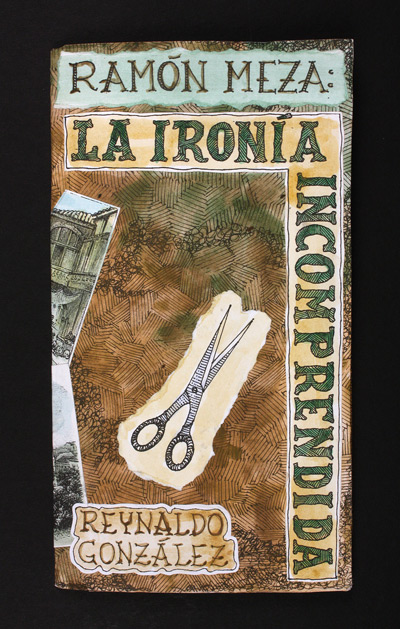

Ramón Meza: La ironía incomprendida [Ramón Meza: The misunderstood irony]

by Reynaldo González

Rolando Estévez Jordán (designer, draftsman and calligrapher)

Laura Ruiz (editor)

Matanzas, Cuba: Ediciones Vigía, 2010

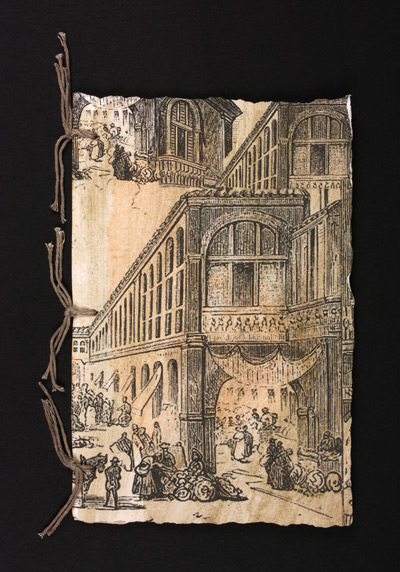

Photocopies on paper with watercolors and string

Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri (2010.10 &b)

Gift of Profs. Juanamaria Cordones-Cook and Michael L. Cook

Lifting the stiffened brown paper that composes of this tri-fold pamphlet exposes a transcript of a speech by award-winning contemporary Cuban journalist Reynaldo González, entitled Ramón Meza: The Misunderstood Irony. González’s speech focuses on a late nineteenth-century narrative by Cuban author and intellectual Ramón Meza. Meza used the characters in his stories to critique the contemporary aristocracy and highlight Spanish exploitation of Cuban citizens during the colonial period. González asserts that Meza’s work is essential to the formation of Cuban identity, which has unfortunately been misunderstood and underrepresented in Cuban history.

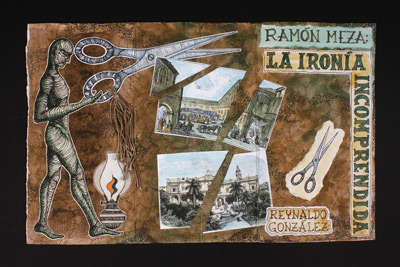

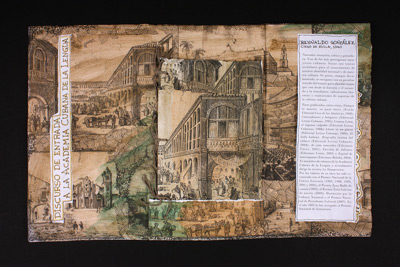

Rolando Estévez, Cuban artist and founder of Vigía press, visually constructs González’s speech through the lens of nineteenth-century Havana architecture. On the exterior of the pamphlet a large unidentified man holds a large pair of scissors. This modern protagonist cuts through pasted images of Plaza Vieja and Plaza de Armas, both located in Old Havana. In contrast, the illustrations on the interior of the pamphlet remain whole, recreating Meza’s nineteenth-century Havana. Replicas of the plazas from the exterior cover, an image of the Plaza de la Catedral, and a bustling contemporary theater are placed amongst bird’s eye views of townspeople dressed in nineteenth-century costume, participating in urban life.

In this context, Cuban architecture represents both the physical and conceptual need for historic restoration. The fractured architecture on the exterior references the actual deterioration of Cuba, calling for preservation. Additionally the severed images expose the detached relationship between colonial and modern Cuban history. This visual statement urges the viewer to link the past with the present and establish a continuous timeline of Cuban identity.

by Alyssa Wolfman

In creating Ramón Meza: The Misunderstood Irony, Cuban artist and founder of Vigía Press Rolando Estévez chose a design that corresponds to a speech of the same title. The speech was written by award-winning contemporary Cuban journalist Reynaldo González, as it was given to the Cuban Academy of Language in 2005.1 Opening the pamphlet-like exterior reveals a transcript of the speech in the form of a removable booklet, tucked into a pocket on the center panel. A long strip of paper attached to the right interior flap provides a short biography of González, declaring him “one of the most prestigious Cuban essayists.” The biography describes González’s work as primarily concerned with Cuban history, cultural traditions, and the formation of national identity. González’s enclosed speech addresses these themes using ideas from a nineteeth-century text by writer, journalist, and literary critic Ramón Meza (1861-1911).

Ramón Meza lived and worked at a time of great political and social unrest in Cuba. During Cuba’s wars for independence from Spain, the first of which was fought from 1869-1878 and the second 1895-1898, Meza completed the work that González analyzes: My Uncle the Employee (1891). Meza, as González asserts, uses the characters in his story to critique colonial life, the aristocracy, the standing bureaucratic structure, and the exploitive nature of Spanish-Cuban relations, often through the use of humor. Some nineteeth-century Cuban critics described Meza’s work as radical, while other saw his efforts as conservative. González’s speech sought to alleviate past misunderstandings by resituating Meza’s work into the conflicting circumstances of his time, highlighting its important contribution to Cuban cultural history.

Estévez visually interpreted Gonzalez's speech through the lens of the Cuban cityscape. When laid flat, the exterior of the pamphlet presents a scene of destruction. On the left, a large unidentified standing man, placed behind the signature Vigía lamp, holds a pair of open scissors. The man cuts through two major colonial public squares. The top image closely resembles the Plaza Vieja, located in Old Havana. Plaza Vieja, dating from as early as the sixteenth century and remodeled in the eighteenth century, was the seat of civic authority from the colonial period to Cuban independence in 1898.2 The lower image is most likely the depiction of the main square Plaza de Armas, also in Old Havana. While the images have been cut, the pieces are still placed closely together with clean edges, indicating the possibility of reconstruction.

Unlike the severed locations on the exterior, the interior illustrations are intact. These scenes transport the viewer back in time, recreating Meza’s 19th century Havana. Replicas of the plazas from the exterior cover, the Plaza de la Catedral, which houses the Havana Cathedral, and an interior scene of a bustling contemporary theater are placed amongst bird’s eye views of townspeople, dressed in nineteenth century costume, and participating in metropolitan life.

The destroyed images on the exterior of the book in juxtaposition with the historic views of the interior could suggest numerous interpretations. The interior could be seen as an allusion to the colonial environment of Meza’s time, while the diagonal cuts across the images of historic plazas might indicate a modern commentary on the deterioration of Old Havana during González’s time, as well as that of Matanzas, home to Vigía press. The destruction of historic Cuban architecture has been a repeated theme for modern Cuban artists, who actively call for restoration.3 Since the mid-1970’s, the Cuban government has answered this call by initiating a preservation campaign to restore important sites such as the Plaza Vieja and promote historic tourism.4

However, in light of the literary context presented by González, Estévez’s choice of architecture may be more closely related to the need for a continuation of Cuban national and intellectual history than to a political call for physical restoration. Scholars have often suggested that early Cuban modernist architects employed aspects of colonial Cuban architecture of the nineteenth century as a means to establish an authentic nationalism.5 A similar continuation of iconography here could be inferred as a parallel statement. The fractured architecture on the exterior may act to expose the detached relationship between historic and modern Cuba. This visual statement urges the viewer to link the past with the present, surpass the boundaries of colonialism and revolution, and imagine an “unbroken line of cultural heritage.”6

by Alyssa Wolfman

- 1 The Cuban Academy of Language is an academic association focused on the use of the Spanish language in Cuban literature and culture.

- 2 Rachel Carley, Cuba: 400 Years of Architectural Heritage (New York: Whitney Library of Design, 1997) 55, 59, 86, 89, 219.

- 3 Rachel Weiss, To and from Utopia in the New Cuban Art (University of Minnesota, 2011) 174-176.

- 4 Carley, Cuba, 209-217.

- 5 Juan Martínez, Cuban Art and National Identity: The Vanguardia Painters, 1927-1950 (Gainesville: University of Florida, 1994) 136-138.

- 6 Carley, Cuba, 217.

- http://www.oldhavanaweb.com. This site has numerous images of each plaza, including a nineteenth-century period drawing which looks similar to the ones in the book.