Pasos, paseos, pasadizos [Paces, promenades, passages]

by César López

Rolando Estévez Jordán (designer and draftsman)

Gladys Mederos (editor)

Matanzas, Cuba: Ediciones Vigía, 2007

Photocopies on paper with watercolor accents and cloth

Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri (2009.21)

Gilbreath-McLorn Museum Fund

Paces, promenades, passages is both the title of the book and its content: a poem. Cuban born poet, Caesar Lopez, a prize-winning and well-loved literary figure, authors the text, which argues destruction is not only bad, but often can result in constructing possibility as well. On the pages of the book both the poem and drawings of a single woman appear. The woman wears a hat and ribbons which tie her to the corners of pages, nooks, and other small spaces which are thus designated as hers. The poem speaks of the cyclical process of construction: “the roads that lead to the city are built with stones of the city itself.”

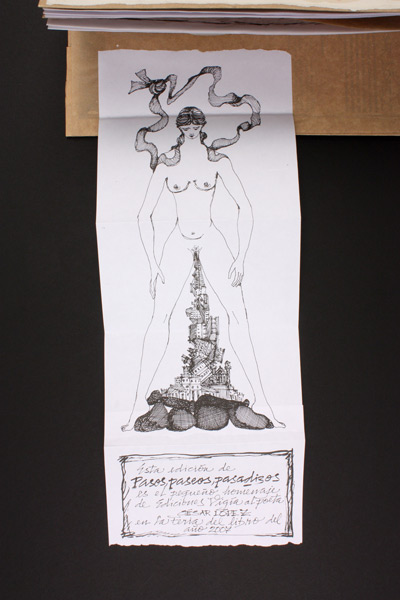

The final page, turned horizontally reveals an appendage, leaf eighteen, that when folded shut closes like an accordion inside the book. To open leaf eighteen, one must lift and gently pull downwards, a similar action to closing a window shade. Fully extended, readers find another image of the same woman. Here revealed nude, standing, and finally free of ribbons, she gives birth to inorganic manmade objects. Unexpectedly but perhaps understandably, cities it seems are "born” or made by the people who live within them, just as the buildings here are delivered from the womb of a human female form. What is born, however, is not a place completely finished but something that is always reconstructing itself.

As readers, we have a relationship with the book that allows us to understand more than what we see. What the eyes alone cannot reveal in Estevez’s images, what Lopez's poem says to us but what its letters and ordered words conceal; rather, we connect through the process of experience and drama. Neither text nor imagery alone could achieve the responses that follow the seamless synthesis of both language and vision. Despite the abstract and complex nature of the concerns raised by the work we connect because complications and starting over are universal human experiences.

by Aimee Koon

Paces, promenades, passages touches on several issues and concerns of contemporary Cuban residents. As indicated by the title, this work describes the measuring of time passing as a mental process experienced physically in built spaces. More broadly put, this work unpacks various concepts of progress. Lopez begins this poem with the evocative verse: “perhaps there will have been / after.” This manipulation of tenses connects the reader, or more appropriately, disconnects the reader, creating a link to a Cuban familiarity with temporal locales.

The text of Lopez’s poem appears alongside the imagery of Estévez in this book published by Ediciones Vigía. The two artists have appeared together previously and a seamless flow is created between the images and the poem’s message. The gutter of the book’s pages, as well as the bottom right and left corners of each page, contains the repeated image of a single woman wearing a hat, which holds the contents of the city. Boulders or other large rocks are an important symbol repeatedly used alongside the woman in the book. What the woman and rocks represent cannot singly be defined or understood: their meanings are much more complex, as is alluded to by the poem’s text. Cuban reporter, Lina de Feria, describes the work as going “beyond the circumstances, and emblems of [them]” rather, the work explores “...our [Cubans’] origin and very existence.”1

Lopez associates the reconstruction and previous destructions of the Cuban built environment as equal to one another. In this poem, he writes, “the road to the city / is made with stones / of the city itself.” Residents of Cuban cities routinely encounter temporal and physical displacement. Even a casual neighborhood stroll can mean a tour of ruins that once were commercial buildings and residences. A simple walk takes one down a road built using cobblestones from an earlier era, a road full of parked boat-sized cars from the 50s and newer models alongside them. The persistent bewilderment can puzzle the internal clock. As humans we crave familiarity and seek to define the world around us as a way to process life experiences. The constant and unnerving presence of liminality as central to one’s identity and community can result in the desire to establish traditions and commonalities. Among artists this needs may manifest itself in the creation of an art that narrates the social and cultural history of a community or nation, as well as makes connections to other places and people both.

Progress in the western world is largely understood to mean advancement, usually in fields or developments perceived to be beneficial to people and civilized society, such as technology or trade. However, due to many reasons, perhaps most notably the trade embargo between Cuba and the United States, Cuba remains fixed in the past, resulting in the construction of a liminal space where previous and contradicting trends in manufacturing, clothing, science, and even art affects accessibility: for Vigía press, access to the materials used for bookmaking, for westerners, a complete picture of the Cuban historical condition.

Ambivalence is a recurring theme in Vigía books. Cuban-born artists working with Ediciones Vigía are fiercely proud to call themselves “Cuban.” This is because Vigía artists are members of a historically insular, now globally aware, community. This collective group consists only of other individuals who likewise understand what it means to remain in a place like Cuba, never to have left it. It can also indicate a repulsion or rejection of negative aspects of Cuban life as well as the rejection of the western understanding of Cuban culture often applied to Cuban artists and their resulting artworks.

Leaf eighteen with foldout extended of woman giving birth to the city of Havana.

*Below is a snapshot of Contemporary Cuba’s built and material environment indicating that these aspects of society are what remains “stuck in the past,” not its people or culture.

March 6, 2007. Havana, Cuba.

- Sources:

- International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism (INTBAU)

- Tour of Cuba, An Introduction to the History of Cuban Architecture and Urbanism Page.

- 1 Cubarte, Columnas Literaria, Dos libros de Cesar Lopez: por la aventura de la poseía.Lina de Feria. 22. September, 2008. http://www.cubarte.cult.cu/periodico/columnas/en-la-arena-literaria/dos-libros-de-cesar-lopez-por-la-aventura-de-la-poes%C3%ADa/87/6832.html