La Revista del Vigía, año 15, no. 27

Rolando Estévez Jordán (designer, draftsman and consulting editor)

Laura Ruiz (director)

Agustina Ponce (consulting editor)

Gladys Mederos (consulting editor)

Leticia Hernández (consulting editor)

Matanzas, Cuba: Ediciones Vigía, not dated

Photocopies on paper with watercolor accents and yarn

Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri (2009.23 a&b)

Gilbreath-McLorn Museum Fund

In an opening letter to the readers of Vigía’s annual journal, editor Laura Ruiz identifies “Travels and the Body” as this issue’s theme. The idea, she confesses, stems from a personal preoccupation with the power of lines. Lines on a map, for example, can bind and articulate the tenuous boundaries of new nations. These same lines can create painful divisions. Most importantly for Ruiz, lines can guide individual bodies on their journeys.

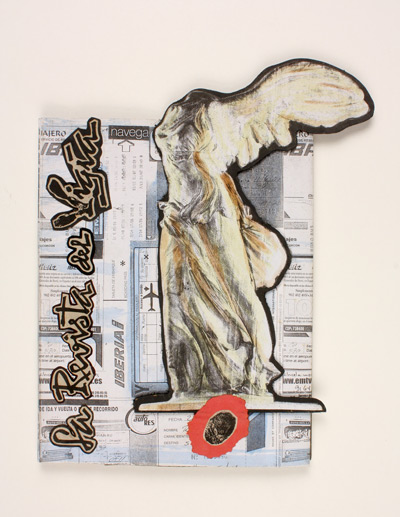

The issue’s imagery evokes Ruiz’s theme of the body in motion. The cover features the Nike of Samothrace embedded in a ground of international airline and bus line tickets. Although Nike is traditionally a Greek symbol of victory, here she functions as a patron goddess of travel. Fleshy traces—footprints, thumbprints, kisses, and even impressions of genitalia—appear throughout the issue, providing indices of now-absent bodies. Although no longer physically present, modern forensics tells us that such marks can be used as evidence to identify and track a person’s movements.

Borders and boundaries are meaningful for Cubans. Since the 1960s, hundreds of thousands of individuals have left the island—some exiled, others seeking refuge. Those individuals who made the journey were divided from Cuba by both physical and emotional borders, leaving an indefinable rift between the Cubans who stayed and those they left behind. Moreover, because Matanzas was dubbed “The Athens of Cuba” in the mid-nineteenth century, the Nike may make reference to the home of the Vigía press. Such classical references collapse the boundaries between the art of ancient Greece and contemporary Cuba.

by Niki Eaton

Laura Ruiz, the director of Vigía’s annual journal, opens this issue with a letter to readers that names “Travels and the Body” as the year’s organizing theme, around which the featured texts were chosen. Ruminating on its origin, Ruiz confesses that the theme was inspired by her personal preoccupation with lines. Lines on a map, she notes, can bind and articulate the tenuous boundaries of new nations. These same lines can be difficult to penetrate, creating painful divisions between loved ones. Most importantly for Ruiz, lines on a map, while seemingly intangible, can guide actual bodies on their journeys.

As promised, the prose, poems, and essays collected in this issue all relate to “Travels and the Body.” While the rest of the pages are bound on the left-hand side in a traditional codex format, the final three poems are printed on a foldout banner with a piece of yarn for hanging. Because the banner breaks with the journal’s layout and intensifies the reader’s participation, it is clear that the poems contained therein, all by the poet Alejandra Pizarnik, are being emphasized. Pizarnik was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, into a family of Eastern European immigrants. She was an avid traveler and successful poet; late in her career she was awarded both a Guggenheim Fellowship as well as a Fulbright Scholarship.1 For this journal, the editors chose poems by Pizarnik that speak of exile and loss. For example, “The Last Innocence” (1956) reads:

To leave

In body and soul

To leave.

To leave

To get rid of the gazes

Oppressive stones

That sleep in the throat

I have to leave […]

Notably, these poems were published posthumously. In 1972, at the age of 36, Pizarnik died of a tranquilizer overdose in Buenos Aires that some suspect was intentional. Although this poem was written years before her death, its content, which is about making the difficult decision to leave “in body and soul,” would have taken on a new resonance for the Vigía editors after her death.

The journal’s visual elements further evoke “Travels and the Body.” Fleshy traces—footprints, thumbprints, kisses, and even impressions of genitalia—appear throughout the issue, providing indices of now-absent bodies. Although the person to whom a print belongs may no longer be physically present, modern forensics tells us that such marks can be used to identify and track the owner and his/her movements. Throughout the journal, the written passages are encircled by fingerprinted borders interspersed with hand-written words for modes of travel (i.e. “horse,” “wagon,” and “foot”). The issue’s cover features the Nike of Samothrace, a Hellenistic Greek statue, embedded in a ground of international airline and bus line tickets. Although the winged Nike is traditionally associated with victory, her surroundings cause her to function as a sort of patron goddess of travel. Appropriated sculptures from antiquity—including Aphrodite (the goddess of love), Ares (her consort), along with various unnamed atheletes—are illustrated throughout, conjuring associations with Greek travel epics. The Odyssey, for example, would be a particularly powerful association for Cubans as a story about finding one’s way home.

Indeed, borders, boundaries, and journeys are meaningful for Cubans. Since the 1960s, hundreds of thousands of individuals have left the island by air or sea—some exiled, others eagerly seeking refuge from communism and an unstable economic climate.2 Those individuals who made the journey were divided from Cuba by both physical and emotional borders; their leaving created an indefinable rift between the Cubans who stayed and those they left behind.3 The imagery takes on new meanings when inflected by this context. For example, according to Greek mythology, Aphrodite was ‘born of the seafoam’ and carried to the shore by ocean waves. As the sea embodied, Aphrodite becomes a mournful symbol of loss and separation as well as an emblem of national island pride. In addition to the journal’s Cuban associations, the Greek imagery also likely alludes to the city of Matanzas, the home of the Vigía press, which was dubbed “The Athens of Cuba” in the mid-nineteenth century.4 In this way, Vigía’s classical references collapse the geographic and temporal boundaries between the culture of ancient Greece and contemporary Cuba.

by Niki Eaton

- 1 Alejandra Pizarnik, Alejandra Pizarnik: a profile, edited with an introduction by Frank Graziano, and with additional translations by Suzanne Jill Levine (Logbridge-Rhodes, 1987).

- 2 Richard Gott, Cuba: A New History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004).

- 3 Linda S. Howe, Transgression and Conformity: Cuban Writers and Artists After the Revolution (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004).

- 4 Miguel A. Bretos, Matanzas: The Cuba Nobody Knows (Gainseville: University Press of Florida, 2010) 102.