What mystery pervades a well!

by Emily Dickinson

Manuel Darío García (designer and draftsman)

Matanzas, Cuba: Ediciones Vigía, not dated

Photocopies on paper with watercolor accents

Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri (2009.76)

Gilbreath-McLorn Museum Fund

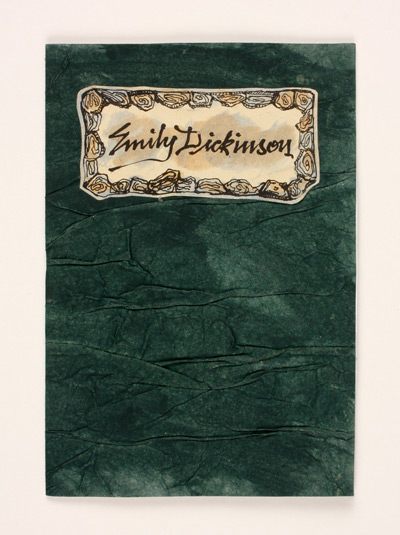

A simple construction contradicts the complexity of the poem and image inside of this folio. Manuel Dario Garcia designed the exterior to mimic a traditional nineteenth-century book binding. The hue of the green watercolor and visual texture of the hardened paper reminds the eye of cracked, dyed leather, but upon physical contact, the user understands the decoupage paper construction. An artificially aged slip of paper inside contains a handwritten version of the poem, What mystery pervades a well!

A watercolor paper label announces the author’s name, Emily Dickinson, written in a scrawling hand and surrounded by a stone-like, circular border. The border isolates her name from the field of green. The wall of stone represents the isolation of Dickinson, as famous for cloistering herself away from the world as for her poetry. Contemporary Cuban artists also experience a sense of isolation due to the restrictions often placed on them by the cultural ministry.

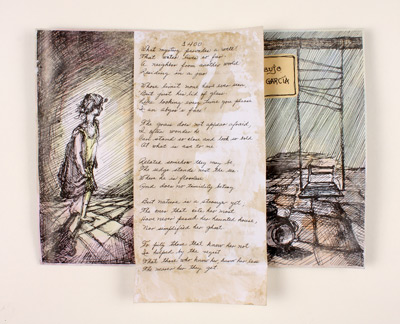

As an island, Cuba is isolated from other cultures.The sea separates the Cuban people from the outside world; people leave via the sea and don’t return. Famously, Dickinson isolated herself from the outside world and this is reflected in the words of her poem. She describes looking into the watery depths of the well: “But nature is a stranger yet…to pity those that know her not is helped by the regret that those who know her, know her less the nearer they get.” The image inside the folio expresses a feeling of isolation. A lone, young woman pensively holds her skirts while she looks longingly at deep, empty space lit by a powerful, unseen source.

The image of the young woman evokes a sense of waiting for the return of someone or something absent or distant. The imagery connects to the mood of Dickinson’s text; she writes, “The water lives so far away, like a neighbor from another world.” Following the girl’s stare, the viewer looks to the back of the folio and finds only the uncovered Vigía and dying flowers rather than the missing element for which the girl is searching. The sense of longing and isolation characterizes the desire for artistic freedom of both Vigía artists and Dickinson. These artists censored themselves out of fear: the Vigía artists feared retribution from the Cuban government, Dickinson feared literary retribution for her experimental, non-traditional style.

The work of Dickinson, a great American poet, filtered into Cuba through the Cuban literati’s connections to Europe and Latin America in the early twentieth century. Spanish translations of single poems by Dickinson appeared as early as 1917, and a Spanish-language biography of the poet was published in Mexico in 1955. Margarita Ardanaz translated What mystery pervades a well! into Spanish in 2004.

What mystery pervades a well! represents the mystery of Vigía and Dickinson. Both artists express deeply personal components of their identity, isolation and self-censoring, through their imagery. Dickinson uses her words and Manuel Dario Garcia uses his image of a lonely, young woman.

by Sarah Jones

Ediciones Vigía’s What mystery pervades a well!, a visual, sensory and temporal enigma, complicates the viewer’s first impression.The book’s simple construction contradicts the complexity of the poem and image inside. Unlike some of Vigía’s more multifaceted constructions, this straightforward folio consists of front and back hard covers bound in the center with a flexible material. The object, oriented in a vertical manner, replicates the interaction a reader has with a traditional book. Through first impression, this book comforts the user with its ordinariness, but inside the viewer finds an image and text fraught with complexity.

Manuel Darío García designed the exterior to mimic a traditional nineteenth-century book binding. The variegated hue of the green watercolor and visual texture of the hardened paper reminds the eye of cracked, dyed leather, but upon physical contact, the user understands the decoupage paper construction. The wrinkles of stiffened paper create peaks and valleys that ebb and flow as the user runs their hand over the folio cover. The appearance of a nineteenth-century book mimics bindings that may have covered Dickinson’s works had her poems been published in her life time.

A watercolor paper label announces the author’s name, Emily Dickinson, written in a scrawling hand and surrounded by a stone-like, circular border. The border isolates her name from the field of green. The wall of stone represents the isolation of Dickinson, as famous for cloistering herself away from the world as her poetry. Contemporary Cuban artists also experience a sense of isolation due to the restrictions often placed on them by the cultural ministry.

The Vigía lamp occupies the back of the folio’s exterior. The lamp has lost its hurricane glass cover and the flame flares in a wild frenzy that engulfs the name of the publishing house. The same flame casts shadow versions of the lamp’s base and its neighboring containers. The strength of the uncovered flame relates to the source less lamp light on the interior. The tall cylindrical vase holds a slender object, which at first glance appears to be a flower; a second examination shows the viewer a miniature version of a short, wide-brimmed hat, often worn by Cuban peasants (Fig. 1; see below)

A photocopied edition of Garcia’s drawing dominates the interior of the folio. A lone, young woman pensively holds her skirts while she looks longingly at deep, empty space. She ignores the empty swing and collection of jars on the opposite side of the fold. The image invokes a sense of waiting for the return of someone or something absent or distant. The imagery connects to the mood of Dickinson’s text; she writes, “The water lives so far away, like a neighbor from another world.” She desires to know nature and the mystery of the water in the well.

Water and the sea are a common theme among the works of Ediciones Vigía. As an island, Cuba connects to the sea in a significant manner. Dickinson wonders about the relationship between human and nature: “But nature is a stranger yet…to pity those that know her not is helped by the regret that those who know her, know her less the nearer they get.” Water is a life-giving force. Deprivation of water leads to devastating consequences for all living beings as symbolized by the dried flowers held by the tall vase in the center of the interior image. In 2008, David D’Arcy wrote, “Images of boats and the horizon are a relative constant in Cuban art. For Cubans they’re often an expression of longing for life beyond a geographically and politically enclosed space.”1 As an island, Cuba is isolated from other cultures. The sea separates the Cuban people from the outside world; people leave via the sea and don’t return.

Dickinson and the Vigía artists share a predilection for experimentation with poetic form. The nineteenth-century American poet’s style has been described as “experimental…her poetic power lay in her ability to use an everyday backdrop to present complex ideas in sharp-edged, compact stanzas.”2 The Vigía artists use everyday objects and outmoded manufacturing techniques to express their complex relationship with Cuban culture. The poetry published by Vigía shares an innovative, ahead-of-its-time quality with Dickinson. The only literary mentor Dickinson discussed her work with cautioned her against publication because he “felt that she was unclassifiable within the poetic establishment of the day—departing from traditional forms as well as conventions of language and meter, her poems would have seemed odd, even unacceptable, to her contemporary audience.”3

Dickinson and the Vigía artists also share the practice of self-censorship. Scholars have not determined a reason that American poet did not share her work, but have speculated that she feared the rejection of her independent spirit. The Vigía artists censor their work for fear of retribution from the government for their non-conformity.“Feminist scholarship has convincingly demonstrated her resistance to patriarchal authority and stimulated interest in the revolutionary nature of the self presented in her work.”4 This could also be said of the Vigía artists whose work explores both their individuality and their identity as modern Cubans.

The poets associated with Vigía consider themselves outside of the officially sanctioned art establishment of the Cuban government. Dickinson also saw herself as an outsider, a woman with liberated mind unable to express her opinions because of pressures that were outside of her control. “The Dickinson family tradition had prepared the poet for a life of political activity and public service, only to deny her that life because of her sex.”5 Dickinson’s male relatives were politically active public servants who included Dickinson in their discussions at home. In public, the poet had to comport herself as a proper woman. Like the artists of Vigía, through her poetry, she is able to explore her own uniqueness.

Dickinson, an extremely prolific scribe, wrote nearly 1800 poems, some of which were contained in her copious letters to friends and colleagues.6 She personally bound 833 of her handwritten poems into simple bundles called fascicles.7 Only ten of Emily Dickinson’s poems were published during her lifetime and all were published anonymously.8 Her family facilitated the first publication of her work in 1890.9 Dickinson’s work filtered into Cuba through the Cuban literati’s connections to Europe and Latin America. Spanish translations of single poems by Dickinson appeared as early as 1917 and a Spanish-language biography of the poetess was published in Mexico in 1955. Ediciones Vigía previously published Dickinson’s poem “Slant of Light” in 1998.

- 1 David D’Arcy, NYTimes.com, “It’s Not Political. It’s Just Cuba.” http://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/03/arts/design/03darc.html?pagewanted=all.

- 2 Jennifer Yaros, “Nature and the Self: Dickinson, Bishop, Plath, and Oliver.” Valparaiso Poetry Review, ed. Edward Byrne, v. 10, n. 1 (Fall/Winter, 2008-2009) Online. Accessed 15 February 2012.

- 3 Academy of American Poets. “Poets.org Guide to Emily Dickinson’s Collected Poems.” Online. Accessed 12 March 2012. http://www.poets.org/page.php/prmID/308

- 4 Paul Crumbley, “Emily Dickinson.” The Oxford Companion to Women’s Writing in the United States (1995: Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK) Quoted in Modern American Poetry: Emily Dickinson’s Life. Online. http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/a_f/dickinson/bio.htm. Accessed 7 May 2012.

- 5 Crumbley. Online.

- 6 Academy of American Poets. “Emily Dickinson.” http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/155. Online. Accessed 12 March 2012.

- 7 Crumbley. Online.

- 8 Publications in Dickinson’s Lifetime,” Emily Dickinson Museum and Trustees of Amherst College. Online. Accessed 6 May 2012.

- 9 “The Posthumous Discovery of Dickinson’s Poems,” Emily Dickinson Museum and Trustees of Amherst College. Online. Accessed 6 May 2012. http://www.emilydickinsonmuseum.org/posthumous_publication.